Because of the narrowness of the Strait – famously ‘only an arrow-shot in width’ – any ship trying to pass through it had to expose itself to one monster or the other. Jason and his Argonauts only made it through because they were aided by the goddess Thetis. In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus/Ulysses is warned of the dangers of the two by the goddess Circe. Considering Charybdis the worse threat, he sails his ship closer to the mainland, only to see six of his men carried off by Scylla, one by each head. This myth was the source of phrases like ‘to navigate between Scylla and Charybdis’, meaning having to choose between two equal dangers. This in turn was supposedly the origin of the modern idea – now that scarcely any of us automatically ‘gets’ Classical quotes any more, and they usually sound pretentious – of being ‘caught between a rock and a hard place’.

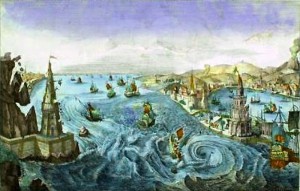

So the Strait of Messina comes with a pretty awe-inspiring build-up. And 18th-century artists, no doubt conscious of an audience who’d all read their Homer, adding in jagged rocks where there are none and unusually fierce, restive waves. Truth is, though, that if you go there today the Strait is one place on earth that seems peculiarly distant from its ancient billing. It is certainly surprisingly narrow: despite the huge size of the island of Sicily, at Messina its closer to the Calabrian mainland than the Isle of Wight is to England, separated from it by just 3–5 kilometres or 2–3 miles of water, but this narrowness only accentuates the Strait’s unthreatening, tranquil ordinariness, criss-crossed by constant ferry traffic. A prosaic, everyday thoroughfare.

The mountains on the Calabrian side are at least suitably abrupt and lofty, but Capo Pelaro or Punta del Faro north of Messina city, the northeastern-most point of Sicily and so supposedly the lair of Charybdis, is a narrow, scrubby sand-spit, backed by a few downmarket beach clubs and discos used by the Messinese on summer weekends, but closed up and deserted most of the year. On an island full of astonishing landscapes, and villages perched incomprehensibly in death-defying cliff top locations, the plainness of this legendary spot seems almost perverse.

Scattered around it are the stubby, neglected remains of a medieval castle, and a coastguard station, but the cape’s biggest ‘sight’ is a huge 1950s electricity pylon, one of the world’s tallest, with over 1,200 steps to the top. For many years electricity was carried to Sicily via this pylon from its twin on the Calabrian side. Their role has long been supplanted by underwater cables, but because of their size the now cable-less pylons have been kept, as monuments. When in power Silvio Berlusconi also repeatedly proclaimed his intention to build a similarly immense, deity-defying bridge across the same location, but now that the Cavaliere is feigning concern for Alzheimer’s patients in a Milan hospice this project seems to have been definitively shelved. Because of the narrowness of the Strait it is apparently true that there are unusual currents and flows within it that do indeed often create small whirlpools near the Point, but nothing big enough to represent a hazard to shipping, even for ancient Greek wooden galleys. There is quite a nice beach, which, since nearly all Sicilians regard it as inconceivable to go anywhere near a beach except in July and August, whatever the sun is doing, you can often have to yourself.

A good place to sit in contemplation, look out for whirlpools, and fill in the legends for yourself as well. For the ancients obviously embroidered a whole lot in search of a good story. But then, that’s what imagination is for.